Living In the Gap: In Conversation with Peter Burr

In January of 2021, between an attempted coup by far-right extremists at the U.S. Capitol and the swearing in of President Biden, artist Peter Burr launched an ambitious multi-part exhibition with Telematic Media Arts in San Francisco: Responsive Eye: An Exhibition in Three Parts.

The exhibition consists of several concurrent installations: Part I: People, Kid Games, and the Infinite at Telematic’s SOMA West gallery space; Part II: Black Square, presented by Telematic at Minnesota Street Project’s Black Box Gallery; and Part III: theshapeofempty.space, presented online with support from Headlands Center for the Arts. Spanning physical and virtual space the exhibition examines contemporary life in the grid. Taking cues from minimalism and op art, the work pushes the limits of a viewer’s perception and awareness, thrusting them into that gap between what is seen and what is felt.

What follows is a conversation between Peter Burr and Daniel Glendening, Communications and Outreach Coordinator at Headlands Center for the Arts. Convening via Zoom, the two talked about Responsive Eye, history, things that are not there, and what it means to be fleshy bodies gathering in digital space.

To get started, I’m hoping that you can give a general overview, from your perspective, of Responsive Eye.

Responsive Eye consists of a body of work that I made essentially since this pandemic started. It’s this ecosystem or set of ideas that I was exploring while in isolation, living in a city where my community does not live, being under a set of physical parameters that require isolation, and therefore having a lens onto the world that is technological. Like, we have the Zooms, we have the—name your internet medium of choice—those become our eyes and ears onto what the world is.

This year I’ve been living in Chicago as a visiting artist at a school—so it’s not fair to say my community does not live here because, in fact, what happened is that I became a part of a community that is academic. That lends a particular way of thinking about what art is that’s historical. I was thinking about minimalism and op art in the middle of the 20th century. There are some intuitive components of those movements that feel interesting right now—for example, we have these digital mediums to communicate to each other through using minimal systems fonts and graphics that have become popular because they’re effective. A bright blue field is really effective at catching your attention—maybe as a moment of pause or maybe just as this thing that can assert its blueness. In that way, an image becomes an icon of itself. It lacks subtlety, right? We don’t think about blue as the color of the sky, we think about blue as this square that’s glowing from our phone.

I’ve been thinking about this lens that I’m viewing the world through, and living through 2020 in Chicago—which is a really racially segregated city—in a moment when there’s a lot of discourse not only around issues of class and race but also basic concerns about how human beings are treated. Thinking about reducing a shape or a color to an icon in the same way that a human body can be reduced to a shape or an icon, I became really interested in this as a sort of a vocabulary. I describe it as a vessel: The Responsive Eye (which refers to a show at the Museum of Modern Art from the mid-20th century that introduced op art to the wider American public). It felt like an interesting vessel to interrogate this tension of nothingness and thingness.

Peter Burr, PEOPLE (screenshot). Software (color, sound) for screen or projector, 2021.

In thinking about that link to history, along with those ties to minimalism and op art, the first place I jump in viewing the work is to suprematism. It’s hinted at through some of the works in this constellation, like Black Square, but also in the mutability of grid forms, the stacking of geometric layers, and the sense of generating a virtual space in a two-dimensional plane. I’m curious about that historical link as well, and maybe how you see connections between suprematism and minimalism or op-art.

The film that’s at Minnesota Street Projects is called Black Square. That’s a reference to Malevich’s Black Square painting which popularly is understood as the first painting of nothing, but I’m also thinking about blackness as a color and about this symbol as something that is unstable, right? While we’re sharing this lockdown in America and in the world, Black Square became something really specific on Instagram that has nothing to do with suprematism or what Malevich was responding to during the sandwich between World Wars and European tension—a completely different set of social conditions that creates a completely different kind of gesture, that perhaps is relating to religion as something to rebel against more than representations of people.

Something that I have a really hard time extracting myself from in this moment as an artist is the fact that even now, people who are reading this conversation are reading it on a grid. Your computer screen is literally a matrix of liquid crystal cubes creating this magical illusion of content, of meaning, of our thoughts, right? I’m looking at you in Zoom, in a box that’s a box of these little boxes. Of course, the company that makes my computer will try to negate that and tell me that this is a “retina display”—they’re going to use metaphors of the human eye to try to negate the grid that is actually manufacturing this image of you.

When I talk about a pure blue field or a pure black field, these are ways of approaching the technology of reproduction in a way that’s cranked up to its extremes. It’s a bunch of squares of a single color lining up into the grid. There’s a very specific set of pixels horizontally and vertically that you can count. There’s a finite amount of those, and there’s a finite amount of blue that you can produce. As an artist exploring what the maximum of those components are, it allows me to play with this vocabulary that can, in some ways, I hope, allow for this unstable relationship with the medium you’re viewing my work on.

Peter Burr, BLACK SQUARE (screenshot). SIngle channel video (color, sound) for screen or projector, 2020.

In my experience with the online exhibition, at times it falls apart—because of internet lag, the animation will stutter. The timing is a mutable thing also.

The plumbing of the internet has a specific capacity that is also optimized for this kind of blurry, earthy, fleshy, melty, cloudy illusion—it’s not trying to assert its grid-ness. If we look back maybe 30 years, those sorts of aesthetics (like early Mac Paint or the Commodore 64) expose a real grid-ness that I find interesting.

When you put a strobe on your screen through the internet, if you have low bandwidth that flicker rate is gonna change—I don’t actually get to predict that. It forces me to think about these objects more as events, in the same way that quantum physicists might ask you to reflect on, say, this glass that I’m holding. I can understand this as an object. I can feel it. I can touch it. But there’s also a way to understand it as an event: this glass is a confluence of the materials that are forming it at this moment, and that’s going to change. This is not permanent in any essential way. That’s tricky, because the history of art, at least in the way that I’ve been thinking about it through this show, is one that is concerned with archiving and preserving—which to be quite frank is just impossible, right? There’s no way! But the human condition has some component that cares about valuing that.

There are other levels of talking about what’s not there—when Bridget Riley, for example, creates a painting, using these greys and these oranges that create these other phantom colors, the colors become unstable because your eyeballs are changing. There’s a way in which as an artist she can point at something that is not there, that is actually within you that you’re seeing.

I also can’t help but draw this connection to a relationship with media writ large. I’ve had so many points during this past year, and still now, feeling mentally unstable experiencing this global pandemic, seeing images of social conditions that are not okay, and then to have them not be talked about, or talked about in a way as if they have no value or they are not there.

In that way, in this exhibition about optical illusions the first thing that perhaps you intuitively recognize is it’s an exhibition about human bodies, but it’s not talked about. It’s this sort of thing that’s existing under the surface, at least rhetorically.

Peter Burr, THE SHAPE OF EMPTY SPACE (screenshot). Online artwork, 2021.

So, thinking about the representation of the figure, there’s a kind of figure asset that seems to exist through a lot of your work: a flattened depiction of a figure. In Responsive Eye they’re depicted in a few places: in the works that are “displayed” there’s a body convulsing either in ecstasy or in anguish, interrupted by these flickering color blocks. There are these bodies that serve as a surrogate audience to that projection; as a user I have some control over them and can click on them and they collapse. There’s a kind of accrual of these fallen bodies over time. And in the piece “People,” on view at Telematic, these figures are walking off of this cliff and forming this massive, bizarre, colorful stalagmite. I’m curious about what these bodies are for you and what they represent, and also about death, and pain or ecstasy.

In the act of making art there’s an aspect that is about sharing and communication, but there’s also an aspect that is about catharsis. There’s a lot of work that I produce that is motivated by catharsis that does not get shown, because I don’t think that, as a solitary motivation, that’s going to create compelling objects for someone else to gaze at.

If we want to talk about death, and we want to talk about catharsis, there’s a way in which this project or these artworks are simply residue—these artifacts from living through a moment of time in which death is the narrative. We’re still in it—when I go outside after our discussion I’ll put on a mask because of the presence of death, right? That presence is always there. I think that’s one of these things that really drives these debates about COVID, “Well the flu is always there.” It’s true, we are these leaky bodies that are always on the razor thin edge of death. But these silicate bodies that are represented in Responsive Eye, if they’re going to experience death, that actually has to be programmed in. I would argue at no point in the show do you actually have an intimate relationship with the feeling of death.

What I experience in making these works is thinking about these bodies as pieces of material that can accumulate the way that—when learning about COVID and the pandemic or structural issues of class and social oppression, I’m forced to think about people as these abstractions, right? As these numbers. Or when reading a magazine or a newspaper, perhaps an artist has visualized people as some sort of infographic. I’m much more interested in that absence of that feeling of death and what happens when we see these signifiers of death or suffering that have been removed from their emotional valence or their emotional weight.

Peter Burr, KID GAMES (previz). Augmented reality work, software for tablet, 2021.

That’s a sort of alienation from that emotional response. I’m thinking about the Pieter Bruegel painting that you reference a lot, The Triumph of Death. It isn’t explicitly in this exhibition but is hinted at through the accumulation of collapsed bodies—that omnipresence of mortality I guess, but there’s a kind of distance, right?

What’s interesting about the Bruegel painting is that it’s called The Triumph of Death, but if you look at it Death is actually represented as this community of skeletons. It’s a triumph of skellies. It’s kind of cute!It’s something I really love about it, but also as an artist I think that trying to point at the absence of something—what would that painting look like if those skeletons were not there? It would be a bunch of people being assholes to each other. And in that way, there is no antagonist because that’s just human nature.

Peter Burr, A B BODY (four screenshots). Nine-channel video with custom scaffold, 2021.

I’m also curious about the audience’s agency, and the sense of humor to that accumulation of these fallen assets. There’s a kind of guilty joy of clicking on these figures and seeing them pile up and having that bizarre sense of, “Oh, I have control over these things, and it’s my choice whether they stand or collapse.”

That’s one of these tensions that I’m really interested in in this moment. As I think about my relationship to other people through internet-mediated social ecosystems, there is no accountability. In the case of the online exhibit, theshapeofempty.space, there’s a prompt to try to be kind, but if you actually want to do anything beyond just look at the artwork, the one verb that I give to my audiences is “push this person over”! I can remember in the late ‘90s when I was first learning about the internet and using AOL chatrooms, the first thing I did was go onto these chatrooms with my friends and be an asshole to strangers! There is a tension at play when we think “these are people,” rationally, but we don’t actually feel that.

That’s also a form of catharsis too, right, like, having this sort of ability to exert some control or influence over this screen world.

Yeah, where there is no other real control except in shutting the thing off! Yet we’ve become so comfortable living within this space as if it’s natural space. A lot of my students that I talk to about this don’t even think about turning it off. We can talk about it in class but the reality is we’re in class on Zoom, they have their Discord open, they have their other feeds open, their identities are these networked identities, so if you shut that off you shut you shut off —

Yourself, kind of.

A big facet of it!

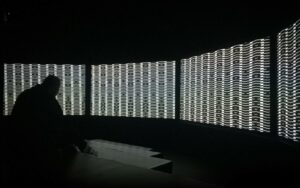

As part of this constellation of projects in Responsive Eye, you included screenings of past video work, including Dirtscraper. There are some pretty dramatic formal leaps in the primary works of Responsive Eye, but also some things that are very closely tied together formally, like the figure asset. How do you think about those pieces nesting together?

In showing Dirtscraper and the Labyrinths screening, we’re talking about the past ten years of work. Labyrinths was a program of six short films screened chronologically; it started with a piece made about ten years ago and ended with the Black Square film that’s installed at Minnesota Street Projects right now. Ten years ago, I was consumed with nihilistic depression and I could not find my way out of it. Thinking about the Labyrinths program, there’s an implicit narrative that is not on the surface: my own journey of finding tools to dig my way out of the self-gazing depressive spiral that was gnawing at all that early work.

Something that I feel happening when I look at the body of work that is Responsive Eye is that there’s this gazing outward, but it’s hitting this surface of nothingness [laughs] and that, in some ways, speaks to the particular social conditions or physical parameters that I live with here in Chicago right now.

While thinking about these possible relationships I started building my own narrative, imagining Responsive Eye as an exhibition that would exist within the world of Dirtscraper, if those citizens held an exhibition. [laughter] And in hearing you talk about your own personal narrative within the work, I’m thinking about hope, and the ability to find hope when worldly conditions seem to be trying to squash it.

It’s elusive.

It’s elusive! And I’m thinking about that glimmer of possible utopian thinking within a dystopic structure.

I love this idea that Responsive Eye happens inside of Dirtscraper!

To talk about hope: that’s a big question! I think a lot about these concepts of utopia and creating spaces where we can actually take care of each other, and build a better world. And yet, I think the Responsive Eye project is a lot about being isolated, and about having an understanding of people not as human beings but as icons or symbols. There’s not a lot that can be done with that to build a better world—it’s unstable material.

As artists we can propose these alternative worlds, or alternative ways of working. Something that I find myself talking about with my students who are making work that’s trying to be critical of the structures we’re a part of is to think, like, where do we find avenues to actually not call this “art,” and to just do the work? There’s a piece called Pattern Language that was in the Labyrinths program. I took that title from a book, Pattern Language, that is essentially a textbook about how to build your own world, in a better way, from the scale of a windowsill to the scale of a city. I really like that idea. I like the ambition of “ok, we can actually build this thing!” I think, with Pattern Language, that text can be symbolic and perhaps lead us toward feeling more empowered. But it is didactic in this way. It is a textbook, and Responsive Eye is not a textbook.

Peter Burr, DIRTSCRAPER. Installed at The Sundance Film Festival, Park City, Utah, 2019.

Thinking about some of your earlier work generating spaces for collective experiences, I’m curious about how you’re thinking about individual experience through the screen versus collective experience in a space—about that relation and how one might serve as a gateway to another?

I was talking with a friend of mine who’s also teaching right now and we were lamenting the situation our students are in. One of my friend’s students talked about how every morning they wake up, they take their shower, they coat themselves with coconut oil, and they’re there in Zoom. And my friend had this realization: “Oh, this is something that I’ll never have access to about this person: the way that they smell.”

There’s so much more to the experience of being in the world than can be reproduced through an image, or even a video or a VR experience. There are all these multisensorial details that the 99% of our human brain that doesn’t go through our conscious perception is absorbing. Beyond the social conditions of an art show is just that feeling of a thing, in which you understand and you know that this is. This is the world that I live in. I think one of the really difficult things about this moment in time is that our—or I can say “my”—my conscious understanding of the world that I live in is really, really different from the world that I feel like I’m living in.

There’s a similar tension when I make a digital art show and I couple it with a real art show—I haven’t actually seen the art show. I have no idea what that show is like! All that I’m left with is that gap, or that feeling, of “I know that this show exists, but I don’t feel that it exists.”

Within that—let’s call it the online or virtual space—to also have a show in that space becomes a site where I can hopefully be playful, and I can hopefully reconcile some of the sadness of living in that gap.

Peter Burr, PATTERN LANGUAGE. Single channel video (b+w, sound) for screen or projector, 2017. Pictured installed at Muziekgebouw aan ‘t IJ in Amsterdam, NL

Ok, last question, and I probably already know the answer to this, but: what’s your favorite science fiction film?

[laughs] I feel like I should say something other than Stalker! But, let me talk about Stalker: I think Stalker is really compelling because it’s kind of not a science fiction film.

Another film I like is Hard to be a God—I believe it’s also based on a text by the Strugatsky brothers. It has a similar quality, but instead of taking place, like Tarkovsky’s Stalker, in a late ‘70s post-industrial hellscape, it takes place in this kind of medieval space. It’s trying to imply that it takes place on another planet and that as human beings, as we congregate on this planet, we have to trace our way through all the hells of history as we did on planet Earth, and this film takes place in this kind of earthy medieval moment. There’s a density to that, there’s this—

A “Bruegel-ness,” maybe?

[laughs] There’s a Bruegel-ness, a brutal Bruegel-ness to it that I find really compelling. Yeah, thinking about these science fiction films that are also not too distant feels really interesting to me.

Peter Burr, BLACK SQUARE (screenshot).

Peter Burr’s Responsive Eye: An Exhibition in Three Parts, is presented by Telematic Media Arts, with support from Headlands Center for the Arts, Minnesota Street Project, and California College of the Arts. Part I: People, Kid Games, and the Infinite was on view January 15th–February 20th at Telematic Media Arts. Part II: Black Square, presented by Telematic Media Arts at Minnesota Street Project’s Black Box Gallery, is on view through March 27th,at 1275 Minnesota St in San Francisco. Part III: theshapeofempty.space, co-presented by Telematic Media Arts and Headlands Center for the Arts, is on view through March 27th online at theshapeofempty.space.