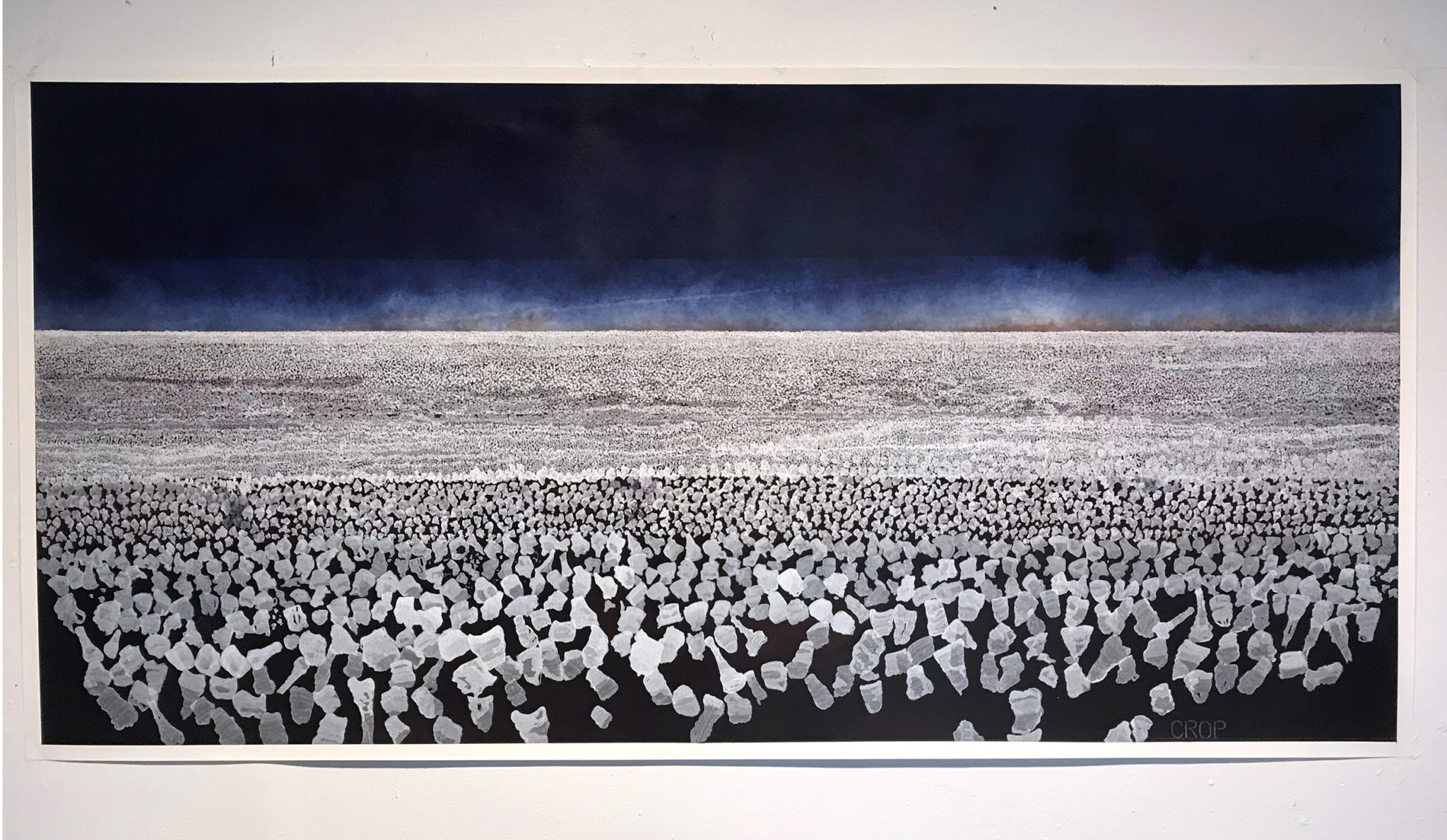

Rodney Ewing, "High Cotton," 2018; acrylic and dry pigment on paper; 45 x 90 in.

Rodney Ewing

Artist Statement

While debating demanding topics such as race, religion, or war, it is simple enough to become polarized and see situations in either black or white, right or wrong. These tactics may satisfy individuals whose position depends on employing policies or implementing strategies that promote specific agendas for a specific constituency. But as an artist, it is more important to create a platform that moves us past alliances and begins a dialogue that informs, questions, and in some cases even satires our divisive issues. Without this type of introspection, we are in danger of having apathy rule our senses. We can easily succumb to a national mob mentality and ignore individual accounts and memories. With my work I am creating an intersection where body and place, memory and fact are merged to re-examine human interactions and cultural conditions to create a narrative that requires us to be present and profound.

While at Headlands

While in residence, I will begin a body of work, “The Devil Finds Work”, the title taken from the a group of essays by James Baldwin on identity and racism in the American movie industry, documenting how the Black Body has had to navigate physical, social, and psychological spaces in America. The series will include drawings and an installation that document Black communities’ history of survival techniques and its continued struggle for autonomy over its physical and spiritual being. With the escalating assaults on the Black community by individuals, law enforcement, and institutions, my community has been discussing how to operate in these violent times—not only for our physical well being, but also for our peace of mind. The African American community has always given their children “The Talk,” a set of social instructions about how to survive encounters with law enforcement and private citizens. However, with events including the murders at the hands of police of Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, and Philando Castille, and the death of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman, these operating instructions are becoming obsolete. The feeling of entitlement over the Black Body has violated mundane pursuits, such as waiting for a friend in Starbucks, sleeping in a college common space, and walking into one’s own apartment building. So how does a body take precautions when the rules of engagement are constantly shifting? How do you instruct the next generation to survive, when any perceived offense ends in an execution? How do you embrace the history of your identity, when a large part of it has been marred by violence?